Sa skya paN+Di ta: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (6 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Person | {{Person | ||

|HasDrlPage=Yes | |HasDrlPage=Yes | ||

|HasLibPage=Yes | |HasLibPage=Yes | ||

|HasDnzPage=Yes | |HasDnzPage=Yes | ||

|HasBnwPage=Yes | |HasBnwPage=Yes | ||

|PersonType=Classical Tibetan Authors | |||

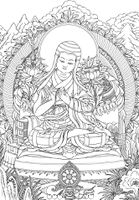

|images=File:Sakya Pandita (R. Beer).jpg{{!}}Line Drawing by Robert Beer Courtesy of [http://www.tibetanart.com/ The Robert Beer Online Galleries] | |||

|MainNamePhon=Sakya Paṇḍita | |MainNamePhon=Sakya Paṇḍita | ||

|SortName=Sakya Paṇḍita | |||

|MainNameTib=ས་སྐྱ་པཎྜི་ཏ་ | |MainNameTib=ས་སྐྱ་པཎྜི་ཏ་ | ||

|MainNameWylie=sa skya paN+Di ta | |MainNameWylie=sa skya paN+Di ta | ||

|AltNamesWylie=kun dga' rgyal mtshan; sa skya paN+Di ta kun dga' rgyal mtshan | |AltNamesWylie=kun dga' rgyal mtshan; sa skya paN+Di ta kun dga' rgyal mtshan | ||

|AltNamesTib=ཀུན་དགའ་རྒྱལ་མཚན་; ས་སྐྱ་པཎྜི་ཏ་ཀུན་དགའ་རྒྱལ་མཚན་ | |AltNamesTib=ཀུན་དགའ་རྒྱལ་མཚན་; ས་སྐྱ་པཎྜི་ཏ་ཀུན་དགའ་རྒྱལ་མཚན་ | ||

|AltNamesOther=Sapaṇ; Sapen | |AltNamesOther=Sapaṇ; Sapen; Sapan | ||

|YearBirth=1182 | |YearBirth=1182 | ||

|YearDeath=1251 | |YearDeath=1251 | ||

|TibDateGender=Male | |TibDateGender=Male | ||

|TibDateDeathGender=Female | |||

|TibDateElement=Water | |TibDateElement=Water | ||

|TibDateDeathElement=Iron | |||

|TibDateAnimal=Tiger | |TibDateAnimal=Tiger | ||

|TibDateDeathAnimal=Pig | |||

|TibDateRabjung=3 | |TibDateRabjung=3 | ||

|TibDateDeathRabjung=4 | |TibDateDeathRabjung=4 | ||

|ReligiousAffiliation=Sakya | |ReligiousAffiliation=Sakya | ||

|PersonalAffiliation=Grandson of [[Sa chen kun dga' snying po]] and nephew of [[rje btsun grags pa rgyal mtshan]] and [[bsod nams rtse mo]], and uncle of [[chos rgyal 'phags pa]]. | |PersonalAffiliation=Grandson of [[Sa chen kun dga' snying po]] and nephew of [[rje btsun grags pa rgyal mtshan]] and [[bsod nams rtse mo]], and uncle of [[chos rgyal 'phags pa]]. | ||

|StudentOf= | |StudentOf=Śākyaśrībhadra; rje btsun grags pa rgyal mtshan; | ||

|TeacherOf=gu ru chos kyi dbang phyug; chos rgyal 'phags pa; yang dgon pa rgyal mtshan dpal | |TeacherOf=gu ru chos kyi dbang phyug; chos rgyal 'phags pa; yang dgon pa rgyal mtshan dpal; lho pa kun mkhyen rin chen dpal | ||

|BdrcLink=https://www.tbrc.org/#!rid=P1056 | |BdrcLink=https://www.tbrc.org/#!rid=P1056 | ||

|TolLink=http://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Sakya-Pan%E1%B8%8Dita-Kunga-Gyeltsen/2137 | |TolLink=http://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Sakya-Pan%E1%B8%8Dita-Kunga-Gyeltsen/2137 | ||

|tolExcerpt=Sakya Paṇḍita Kunga Gyaltsen, commonly referred to as Sapaṇ, was the fourth of the Five Patriarchs of Sakya and the sixth Sakya throne holder. A member of the illustrious Khon family that established and controlled the Sakya tradition, he was an advocate for strict adherence to Indian Buddhist traditions, standing in opposition to Chinese or Tibetan innovations that he considered corruptions. In this regard he was a major player in what has been termed the Tibetan Renaissance period, when there was a move to reinvigorate Tibetan Buddhism’s connections to its Indian antecedents. He was instrumental in transmitting the Indian system of five major and five minor sciences to Tibet. As an ordained monk, Sapaṇ was instrumental in laying the groundwork for adherence to the Vinaya at Sakya Monastery, built under his successors. He authored more than one hundred texts and was also a prolific translator from Sanskrit. His writings are among the most widely influential in Tibetan literature and prompted commentaries by countless subsequent authors. Sapaṇ’s reputation as a scholar and Buddhist authority helped him forge close ties with powerful Mongols, relations that would eventually lead to the establishment of Sakya Monastery and its position of political power over the Thirteen Myriarchies of central Tibet. | |tolExcerpt=Sakya Paṇḍita Kunga Gyaltsen, commonly referred to as Sapaṇ, was the fourth of the Five Patriarchs of Sakya and the sixth Sakya throne holder. A member of the illustrious Khon family that established and controlled the Sakya tradition, he was an advocate for strict adherence to Indian Buddhist traditions, standing in opposition to Chinese or Tibetan innovations that he considered corruptions. In this regard he was a major player in what has been termed the Tibetan Renaissance period, when there was a move to reinvigorate Tibetan Buddhism’s connections to its Indian antecedents. He was instrumental in transmitting the Indian system of five major and five minor sciences to Tibet. As an ordained monk, Sapaṇ was instrumental in laying the groundwork for adherence to the Vinaya at Sakya Monastery, built under his successors. He authored more than one hundred texts and was also a prolific translator from Sanskrit. His writings are among the most widely influential in Tibetan literature and prompted commentaries by countless subsequent authors. Sapaṇ’s reputation as a scholar and Buddhist authority helped him forge close ties with powerful Mongols, relations that would eventually lead to the establishment of Sakya Monastery and its position of political power over the Thirteen Myriarchies of central Tibet. | ||

|HarLink=https://www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setID=325 | |HarLink=https://www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setID=325 | ||

|PosBuNayDefProv=Provisional | |PosBuNayDefProv=Provisional | ||

|PosBuNayDefProvNotes=*[[Kano | |PosBuNayDefProvNotes=*[[Kano, K.]], ''[[Buddha-Nature and Emptiness]]'', p. 309. | ||

*"As a proponent of the Madhyamaka view of the emptiness of inherent existence privileging the ''Madhyamakāvatāra'', Sapen strongly argues against the tathāgata-essence concept that is central in the ''Uttaratantra''. In his important work, ''Distinguishing the Three Vows'', Sapen shows that the ''Uttaratantra'' requires interpretation." [[Wangchuk, Tsering]], ''[[The Uttaratantra in the Land of Snows]]'', p. 26. | *"As a proponent of the Madhyamaka view of the emptiness of inherent existence privileging the ''Madhyamakāvatāra'', Sapen strongly argues against the tathāgata-essence concept that is central in the ''Uttaratantra''. In his important work, ''[[Distinguishing the Three Vows]]'', Sapen shows that the ''Uttaratantra'' requires interpretation." [[Wangchuk, Tsering]], ''[[The Uttaratantra in the Land of Snows]]'', p. 26. | ||

*"In verses 138-42 of ''Distinguishing the Three Vows'', Sapen further argues that the tathāgata-essence teaching in the ''Uttaratantra'' and other works of the tathāgata-essence literary corpus are provisional, because it meets the three criteria that are characteristics of the Buddha's provisional teachings. The three criteria are the point of reference (''dgongs gzhi''), purpose (''dgos pa''), and counter to the fact (''dngos la gnod byed'')." [[Wangchuk, Tsering]], ''[[The Uttaratantra in the Land of Snows]]'', p. 27. | *"In verses 138-42 of ''Distinguishing the Three Vows'', Sapen further argues that the tathāgata-essence teaching in the ''Uttaratantra'' and other works of the tathāgata-essence literary corpus are provisional, because it meets the three criteria that are characteristics of the Buddha's provisional teachings. The three criteria are the point of reference (''dgongs gzhi''), purpose (''dgos pa''), and counter to the fact (''dngos la gnod byed'')." [[Wangchuk, Tsering]], ''[[The Uttaratantra in the Land of Snows]]'', p. 27. | ||

|PosAllBuddha=Qualified No | |PosAllBuddha=Qualified No | ||

|PosAllBuddhaNote=There is some discrepancy between Sapen's use of the term tathāgata-essence and buddha-nature and other thinkers that use these terms synonymously. In Sapen's view, sentient beings do not possess the former, but do possess a more general form of the latter. So while the answer is a qualified "no" in terms of the more general debate on this issue and the way others have addressed it and asserted Sapen's position, strictly speaking from Sapen's view the answer could more accurately be a qualified "yes" as he does state all beings have a basic "inherent" buddha-nature, though this does not correspond to an essence that is endowed with enlightened qualities. The tricky issue being the equivalency of these terms tathāgata-essence and buddha-nature and the perception of the Sakya position by later authors. | |PosAllBuddhaNote=There is some discrepancy between Sapen's use of the term tathāgata-essence and buddha-nature and other thinkers that use these terms synonymously. In Sapen's view, sentient beings do not possess the former, but do possess a more general form of the latter. So while the answer is a qualified "no" in terms of the more general debate on this issue and the way others have addressed it and asserted Sapen's position, strictly speaking from Sapen's view the answer could more accurately be a qualified "yes" as he does state all beings have a basic "inherent" buddha-nature, though this does not correspond to an essence that is endowed with enlightened qualities. The tricky issue being the equivalency of these terms tathāgata-essence and buddha-nature and the perception of the Sakya position by later authors. | ||

|PosAllBuddhaMoreNotes=*"In verses 59-63 of Sapen's ''Distinguishing the Three Vows'', he argues against the presentation of the existence of a tathāgata-essence or sugata-essence endowed with enlightened qualities in sentient beings. Sapen demonstrates that such a position would be tantamount to holding the view of the Sāṃkhya School, that the "result is present in its cause." [[Wangchuk, Tsering]], ''[[The Uttaratantra in the Land of Snows]]'', p. 27. | |PosAllBuddhaMoreNotes=*"In verses 59-63 of Sapen's ''Distinguishing the Three Vows'', he argues against the presentation of the existence of a tathāgata-essence or sugata-essence endowed with enlightened qualities in sentient beings. Sapen demonstrates that such a position would be tantamount to holding the view of the Sāṃkhya School, that the "result is present in its cause." [[Wangchuk, Tsering]], ''[[The Uttaratantra in the Land of Snows]]'', p. 27. | ||

*"It is evident from ''Distinguishing the Three Vows'' that the tathāgata-essence endowed with enlightened qualities does not exist in sentient beings. But does that mean that Sapen completely rejects the existence of tathāgata-essence in sentient beings?" [[Wangchuk, Tsering]], ''[[The Uttaratantra in the Land of Snows]]'', pp. 27-28. | *"It is evident from ''[[Distinguishing the Three Vows]]'' that the tathāgata-essence endowed with enlightened qualities does not exist in sentient beings. But does that mean that Sapen completely rejects the existence of tathāgata-essence in sentient beings?" [[Wangchuk, Tsering]], ''[[The Uttaratantra in the Land of Snows]]'', pp. 27-28. | ||

*"In ''Distinguishing the Three Vows'', Sapen argues that tathāgata-essence, sugata-essence, buddha-essence, and buddha-element are synonyms, but, interestingly, he never mentions the associated term "buddha-nature" in this context. However, in his ''Illuminating the Thoughts of the Buddha'' (''thub pa'i dgongs pa rab tu gsal ba''), Sapen explains buddha-nature in this way: "The inherent [buddha-]nature exists in all sentient beings. The developmental [buddha-]nature exists [from the time that] one has developed bodhicitta. [The latter] does not exist in those who have not developed [bodhicitta]....So Sapen obviously has a problem accepting tathāgata-essence teachings as definitive, whereas he has no issue asserting that buddha-nature exists in all beings." [[Wangchuk, Tsering]], ''[[The Uttaratantra in the Land of Snows]]'', p. 28. | *"In ''Distinguishing the Three Vows'', Sapen argues that tathāgata-essence, sugata-essence, buddha-essence, and buddha-element are synonyms, but, interestingly, he never mentions the associated term "buddha-nature" in this context. However, in his ''Illuminating the Thoughts of the Buddha'' (''thub pa'i dgongs pa rab tu gsal ba''), Sapen explains buddha-nature in this way: "The inherent [buddha-]nature exists in all sentient beings. The developmental [buddha-]nature exists [from the time that] one has developed bodhicitta. [The latter] does not exist in those who have not developed [bodhicitta]....So Sapen obviously has a problem accepting tathāgata-essence teachings as definitive, whereas he has no issue asserting that buddha-nature exists in all beings." [[Wangchuk, Tsering]], ''[[The Uttaratantra in the Land of Snows]]'', p. 28. | ||

|PosYogaMadhya=Madhyamaka | |PosYogaMadhya=Madhyamaka | ||

| Line 43: | Line 44: | ||

|PosZhenRangNotes=He predates the distinction but is clearly in line with the rangtong perspective. | |PosZhenRangNotes=He predates the distinction but is clearly in line with the rangtong perspective. | ||

|PosAnalyticMedit=Analytic Tradition | |PosAnalyticMedit=Analytic Tradition | ||

|PosEmptyLumin= | |PosEmptyLumin=Tathāgatagarbha as the Emptiness That is a Non-implicative Negation (without enlightened qualities) | ||

|PosEmptyLuminNotes="An opinion shared by rNgog and Sapan is that Buddha-nature should be understood in the sense of emptiness. The difference is that rNgog directly equates Buddha-nature with emptiness, whereas | |PosEmptyLuminNotes="An opinion shared by rNgog and Sapan is that Buddha-nature should be understood in the sense of emptiness. The difference is that rNgog directly equates Buddha-nature with emptiness, whereas Sapan regards the intentional ground (''dgongs gzhi'') of Buddha-nature to be emptiness." [[Kano, K.]], ''[[Buddha-Nature and Emptiness]]'', pp. 309-310. | ||

|IsInGyatsa=No | |||

|PosSvataPrasa=Prāsaṅgika (ཐལ་འགྱུར་) | |PosSvataPrasa=Prāsaṅgika (ཐལ་འགྱུར་) | ||

}} | }} | ||

Latest revision as of 14:52, 10 July 2020

| PersonType | Category:Classical Tibetan Authors |

|---|---|

| MainNamePhon | Sakya Paṇḍita |

| MainNameTib | ས་སྐྱ་པཎྜི་ཏ་ |

| MainNameWylie | sa skya paN+Di ta |

| SortName | Sakya Paṇḍita |

| AltNamesTib | ཀུན་དགའ་རྒྱལ་མཚན་ · ས་སྐྱ་པཎྜི་ཏ་ཀུན་དགའ་རྒྱལ་མཚན་ |

| AltNamesWylie | kun dga' rgyal mtshan · sa skya paN+Di ta kun dga' rgyal mtshan |

| AltNamesOther | Sapaṇ · Sapen · Sapan |

| YearBirth | 1182 |

| YearDeath | 1251 |

| TibDateGender | Male |

| TibDateElement | Water |

| TibDateAnimal | Tiger |

| TibDateRabjung | 3 |

| TibDateDeathGender | Female |

| TibDateDeathElement | Iron |

| TibDateDeathAnimal | Pig |

| TibDateDeathRabjung | 4 |

| ReligiousAffiliation | Sakya |

| PersonalAffiliation | Grandson of Sachen Kunga Nyingpo and nephew of rje btsun grags pa rgyal mtshan and bsod nams rtse mo, and uncle of chos rgyal 'phags pa. |

| StudentOf | Śākyaśrībhadra · rje btsun grags pa rgyal mtshan |

| TeacherOf | gu ru chos kyi dbang phyug · chos rgyal 'phags pa · yang dgon pa rgyal mtshan dpal · lho pa kun mkhyen rin chen dpal |

| BDRC | https://www.tbrc.org/#!rid=P1056 |

| Treasury of Lives | http://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Sakya-Pan%E1%B8%8Dita-Kunga-Gyeltsen/2137 |

| Himalayan Art Resources | https://www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setID=325 |

| IsInGyatsa | No |

| PosBuNayDefProv | Provisional |

| PosBuNayDefProvNotes |

|

| PosAllBuddha | Qualified No |

| PosAllBuddhaNote | There is some discrepancy between Sapen's use of the term tathāgata-essence and buddha-nature and other thinkers that use these terms synonymously. In Sapen's view, sentient beings do not possess the former, but do possess a more general form of the latter. So while the answer is a qualified "no" in terms of the more general debate on this issue and the way others have addressed it and asserted Sapen's position, strictly speaking from Sapen's view the answer could more accurately be a qualified "yes" as he does state all beings have a basic "inherent" buddha-nature, though this does not correspond to an essence that is endowed with enlightened qualities. The tricky issue being the equivalency of these terms tathāgata-essence and buddha-nature and the perception of the Sakya position by later authors. |

| PosAllBuddhaMoreNotes |

|

| PosYogaMadhya | Madhyamaka |

| PosZhenRang | Rangtong |

| PosZhenRangNotes | He predates the distinction but is clearly in line with the rangtong perspective. |

| PosAnalyticMedit | Analytic Tradition |

| PosEmptyLumin | Tathāgatagarbha as the Emptiness That is a Non-implicative Negation (without enlightened qualities) |

| PosEmptyLuminNotes | "An opinion shared by rNgog and Sapan is that Buddha-nature should be understood in the sense of emptiness. The difference is that rNgog directly equates Buddha-nature with emptiness, whereas Sapan regards the intentional ground (dgongs gzhi) of Buddha-nature to be emptiness." Kazuo Kano, Buddha-Nature and Emptiness, pp. 309-310. |

| PosSvataPrasa | Prāsaṅgika (ཐལ་འགྱུར་) |

| Other wikis |

If the page does not yet exist on the remote wiki, you can paste the tag |